From Green Biz – June 2020

by Dean Cycon

I felt this a critical piece of journalism in understanding the economics of coffee farming today.

Paying farmers a living wage is essential to ensuring sustainable coffee production.

When you sit back with a good cup of coffee, you will be engulfed in the warmth, aroma, taste, acidity and body of the brew. Yet, swirling beneath the surface all of the major issues of the 21st century — climate change, globalization, immigration, women’s rights and wealth inequity — are being played out in remote coffee villages around the world.

How companies behave in the coffee trade has a direct impact not only on the lives and livelihoods of 28 million coffee farming families but on the welfare of the planet itself. Coffee companies claiming to be “ethical” or “sustainable” that refuse to pay a living wage to the farmers are fueling this longstanding human and environmental crisis.

Changes in rainfall patterns and temperature weaken coffee plants and reduce yields. Climate-enhanced fungi and bacteria decimate coffee plants, leaving families with little or no income for the next five years until new trees can be planted and mature. Larger farm owners must deforest land and plant more coffee to make up for the historically low prices they are receiving from the market. This deforestation inhibits carbon sequestration, which leads to higher temperatures. The cycle is self-fulfilling.

As a result, coffee production will be greatly limited in medium and lower elevations by 2030 to 2050. When production is reduced, farmers may use more chemicals in the growing process, which harms the soil and water sources, further degrading the planet and human health.

Coffee, poverty and migration are also connected. The largest single group of migrants trying to cross the southern border are from Guatemala, and most of them are from the coffee lands of Huehuetenango province. They are unemployed and landless coffee farming families hoping for a better life.

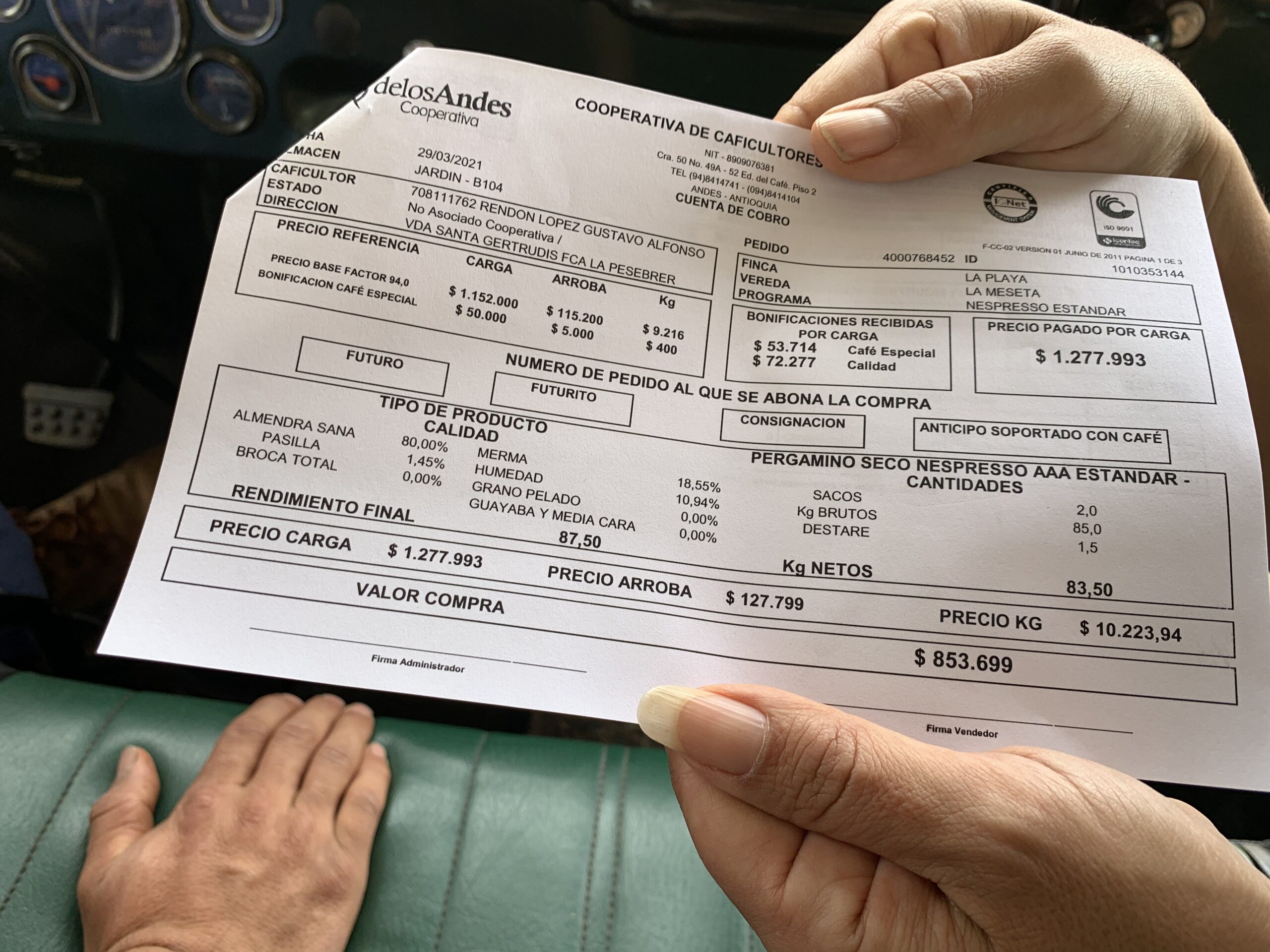

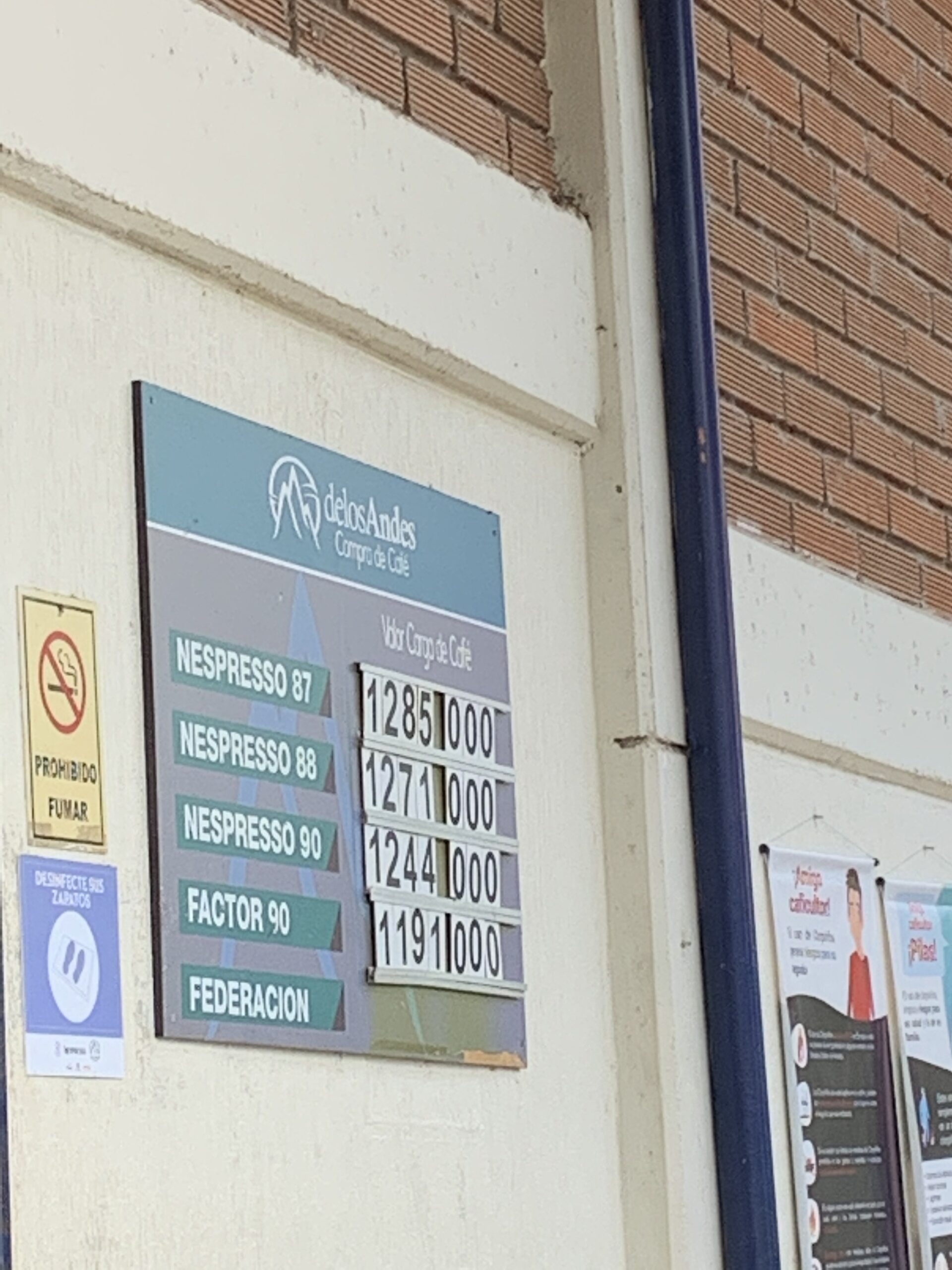

The price per pound paid to coffee farmers is based on the “New York C price,” a commodity system that operates much like a stock market. For several years, the C price for coffee has hovered around the farmer’s cost of production ($0.80-$1.10), which means no profit for the farmers. From a high in 2014, prices paid to farmers have plummeted by 70 percent and now dance around $1 per pound. Every pound a farmer sells, and every cup we drink, pushes a farmer deeper into poverty and despair.

“$1,400 could pay for healthcare, children’s education, proper nutrition and technology to produce higher yields and reduce their need to clear land“

Companies are not required to base their payments to farmers on the C price, and many of us do not. Organic and Bird Friendly certifications offer a price premium to the farmer. Fair Trade provides a “living wage floor” and many committed Fair Traders pay substantially higher prices. The few real Direct Traders offer real price premiums for limited amounts of high-quality coffee. Many companies hide behind labels, such as Rainforest Alliance or Utz Kapeh, or self-created programs such as “Ethical Sourcing,” which sound good but do not guarantee higher prices.

Ironically, coffee company profits may be the highest in history. Companies such as Smuckers and Starbucks continue to raise their prices while their main cost of goods (buying coffee beans) has dropped considerably. According to the United Nations, the ratio between what the farmer was paid and what the companies sold their coffee for was 1:3 during the 1970s. Today, it is as high as 1:20, as many consumers are paying $20 a pound.

In 2012, Starbucks reported its average price for green beans was $2.56 per pound. However, that is the price it paid to the broker, not to the farmer. After backing out shipping, insurance, importer and exporter and mill costs, that price would be closer to $2.20 paid per pound to the farmer. By 2014, Starbucks was only paying $1.72 to the broker (maybe $1.36 to the farmer). By paying the lower amount, Starbucks took $387 million out of the farmers’ pockets. As green prices keep falling, Starbucks has continued to pay coffee farmers less, while charging consumers more.

So, who is winning this game? Not the farmers, not the public and not the environment. Instead of paying enough to support the farmers, large and small coffee companies contribute lesser amounts to nonprofits for clean water, health and environmental projects under the banner of “corporate sustainability.”

If coffee companies really want to fight the difficulties facing coffee farmers and the environment, they should just pay up. If Starbucks returned to its 2012 broker and farmer prices, it nearly would double family income on most small farms. To family farms in Nicaragua, Peru, Ethiopia and Indonesia, that $1,400 could pay for healthcare, children’s education, proper nutrition and technology to produce higher yields and reduce their need to clear land. Even a 25-cent increase in the price paid to farmers, which would get Starbucks closer to the prices paid by truly committed coffee companies, would bring $150 million back to the farms and its stock price would not even blink.

As an industry, we have lived long and well by treating farmers just like coffee. We see them as fungible commodities instead of true partners in the success of our businesses who are integral to effective adaptation to climate change and other issues of the day. The days of maximizing profits without seriously incorporating farmers’ concerns that bind us all together are over. It is time to pay up.